“If the stars should appear one night in a thousand years, how would men believe and adore; and preserve for many generations the remembrance of the city of God which had been shown! But every night come out these envoys of beauty, and light the universe with their admonishing smile.”

― Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nature and Selected Essays

As a admitted science wonk, nerd and overall geek, there isn’t a spacey subject that I won’t read, watch or render an opinion on. I have been to the Houston Space Center, Kennedy Space Center, the Smithsonian, and if I have visited a city with an aerospace museum, I have visited that museum. I own two small telescopes and a tracking device for wide angle DSLR work. I have often gone out into the cold North Dakota nights in the winter trying to teach myself a few new tricks in astrophotography. There is one thing I haven’t had a chance to do, and that is view the heaven’s above through a world class, research grade telescope. Okay, so not that many people EVER have that chance. Thanks to a happy circumstance of training locations, timing and an outstanding public outreach program at a nearby observatory, I did have that chance this last weekend.

McDonald Observatory (http://mcdonaldobservatory.org/), run by the University of Texas – Austin, is located high in the Davis Mountains of southwest Texas. While certainly not the only large observatory in the continental United States, McDonald sits under one of the last remaining patches of truly dark skies left in our country. The facility has a colorful history, having got it’s start back in 1926 when William J. McDonald, a Confederate soldier who had made a small fortune in banking, willed nearly all of his estate to the University of Texas to fund the construction of an observatory. McDonald was a bachelor with no direct heirs, but distant relatives took the will to court trying to negate the $1.1 million (nearly $15 million in 2015 dollars) bequeathment. The case dragged on for years, until eventually Texas settled for $800,000. Still a large sum for the Great Depression and plenty to build a large research telescope. It was, however, a little short on funds to operate the planned observatory. And, at any rate, the University of Texas had no astronomy department.

Enter the second of three key figures in the history of McDonald. Otto Struve was at the time director of the University of Chicago’s Yerkes Observatory (http://astro.uchicago.edu/yerkes/), to this day home of the world’s largest refractor telescope. U Chicago had a large group of astronomers and students, but little capacity to build another large telescope. Taking note of the developments in Texas, Struve guided the institutions into a 30 year agreement that started in 1932. U Texas would build the new scope, and Chicago would operate it. After a few months of site surveys, 6791 foot Mount Locke was selected, and the 82″ telescope, then the second biggest telescope in the world, was dedicated and opened for business on 5 May, 1939.

Left — the 82″ Otto Struve Telescope. The 90,000 lbs. scope is still used for research, and on occasion, public viewing sessions.

Left — the 82″ Otto Struve Telescope. The 90,000 lbs. scope is still used for research, and on occasion, public viewing sessions.

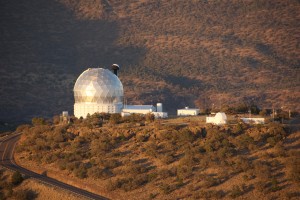

Right — exterior dome.

The telescope did some groundbreaking work over the years — including work by Gerard Kupier, who discovered Miranda (a moon of Uranus) and detected water vapor in the atmosphere of Mars. But by the late 1950’s, with the end of the 30 year agreement with U Chicago coming up, the facility had fallen into a little bit of disrepair. In 1963, the university hired Harlan J. Smith to direct the now independent observatory and create a full fledge Astronomy Department. Smith saw an immediate opportunity in the growing Space Race, and shortly after starting the job secured NASA’s help in planning a new 107′ telescope. When the new scope was completed in 1968, the 320,000 lbs beast was third largest in the world. One of it’s early contributions to science was in a laser range finding program. Days after Apollo 11 headed back from the Moon to Earth, the telescoped fired off a laser at the moon, which reflected off special mirrors left behind on by the Apollo crew and back to the telescope. The measurements had one immediate surprise in store — the Moon was 40 meters further away than anyone had thought. Later studies would show the Moon moving away from Earth at about an inch and a half per year. While the range finding mission has moved off the 107″ scope to a smaller, dedicated 30″ platform, McDonald Observatory continues to operate lasers in this capacity. Beams are routinely bounced off the Moon and Earth orbiting satellites. Our knowledge of the structure of the Moon, as well as our own plate tectonics has improved dramatically from this research.

Left — the 107″ telescope, now named after Harlan J Smith.

Right — exterior shot of the dome shortly after opening for the evening session.

Right — exterior shot of the dome shortly after opening for the evening session.

As the world, astronomy and astrophysics entered the 21st Century, McDonald Observatory, began plans to keep pace. While modern large telescopes can cost a billion dollars or more, McDonald, with the help of four other institutions, designed a unique device that provided massive size for a fraction of the cost. For $13.5 million, the observatory built a scope with an effective diameter of 9.2 meters — 30 feet! How? Well, they set the mirror, actually 91 identical six-sided mirrors, on a platform that is fixed at a 55 degree angle above the horizon. The entire assembly does rotate around it’s dome, and combined with a computerized tracking system suspended above the mirror assembly, seasonal changes and the Earth’s rotation, the Hobby-Eberly Telescope (HET) can cover 70% of the sky visible from it’s position on top Mount Fowlkes.

Left — primary mirror assembly of the 9.2 meter Hobby-Eberly.

Right — external view.

The HET is now completing a major upgrade that will enable it to participate in the search for the elusive component theorized to be powering the expansion of the Universe — Dark Energy. HET also has a twin, the Southern African Large Telescope (SALT) located in Sutherland, South Africa. The exact same design as HET, SALT performs a similar mission and is a partner to McDonald on numerous research projects.

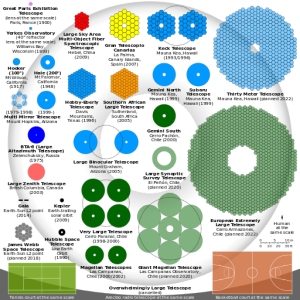

Size comparison of several of the largest telescopes in operation (or planned) today. Wikimedia Commons image.

In addition to the three big telescopes, there are a half a dozen smaller research telescopes on the two peaks, plus a educational visitor’s center at the base of the mountain. McDonald’s public outreach programs shine, and is what attracted me to the facility when I found out I’d be in that part of the country for a few weeks. In addition to public Star Parties every Tuesday, Friday and Saturday nights, the observatory hosts Special Viewing Nights on three of their research telescopes — their 36″, 82″ and 107″ scopes. While my studies here prevented me from spending two nights on the mountain and taking in a Star Party, I made darn sure I could travel there for a Special Viewing Night. Happily, they had one available during my stay on the Struve 82″. Guest for Special Viewing Nights are permitted to stay at the Astronomer’s Lodge, an on site facility used mainly by students and guest researchers. It was kind of dorm room like, but it was comfortable enough considering it is mostly used for sleeping all day long — and it came with home cooked food for dinner!

I drove down Saturday morning, arriving in time to also partake in a Solar Viewing session and a full tour of the Harlan J. Smith telescope and the Gallery of the Hobby-Eberly. The Special Viewing Night commenced at about 7:30 local time, and it was a treat. Most telescopes of this size are not used visually; they are not exactly a back yard Celestron. In fact, the big Hobby-Eberly scope isn’t used for visual observations at all, instead focusing on spectroscopy. Normally the Struve scope is used in a similar fashion, with astronomers sitting in control rooms monitoring computer banks rather than visually looking at the stars. Not on special viewing nights, however. The back of the telescope had a standard 2″ eyepiece connected to it for us to use. Guided by three skilled and knowledgable volunteers (how do I get that gig in a few years?!?) we were taken on a tour of deep space objects. Globular clusters, galaxies and nebulas all stood out in stunning detail.

Above — the view out the dome from behind the 82″ Struve Telescope.

Keep in mind that the human eye is not nearly as capable as high quality cameras, filters and software. When you look through a telescope with your naked eye, you should never expect to see a Hubble Space Telescope image. But this telescope was sharp, and in a common target for small telescopes, M42 The Orion Nebula, stood out in some stunning detail, with the gas of the nebula easily seen. Details were also seen in the Pinwheel Galaxy and many of the other targets. From what the volunteers said, the 82″ is their sharpest visual telescope, even after 78 years in operation. The tour of the cosmos lasted nearly three hours, and after that, we were treated to a site even more stunning — night skies largely devoid of light pollution. There are several nearby towns within 60 miles, but for the most part, the observatory has truly dark skies. After the official tour was complete, I grabbed my DSLR and tripod and took a few images of the skies:

I could honestly write for a few more hours about this one night trip to McDonald Observatory. But the hour is getting late. I may post more about the facility and more detailed information on their current research programs in the coming days. I am also going to seek out other large US observatories and see what kind of public outreach programs they hold. My kids, for one, are not happy I went here without them. So I owe them something similar. I encourage all of you to look into something like this at least once in your life!

Clear skies!